Fire

Europe at night (NASA)

Up until 1881, most theatres in Europe had suffered a fire at one time or another. This was mainly due to the use of oil lamps, candles, or gas flames. Once out of control, flames spread quickly in a building largely made of wood and decorated with textiles, canvas and paper mâché.

In 1881, the Ring Theatre in Vienna (Austria) burned down, leaving about 500 spectators dead. This catastrophe finally changed safety measures and theatre architecture all over Europe:

- new theatres had to be built in three separate parts, each with its own roof and fire-wall

- an iron curtain had to be installed to cut off the stage from the auditorium

- each level of the auditorium had to have its own staircase, clearly marked by emergency exit signs

- all doors had to open to the outside

- all formerly wooden construction elements were to be executed in concrete or metal

- electric light had to be installed everywhere

As cities were not yet electrified, a tailor-made power plant was added to each new theatre – and the age of electricity began.

N.N.

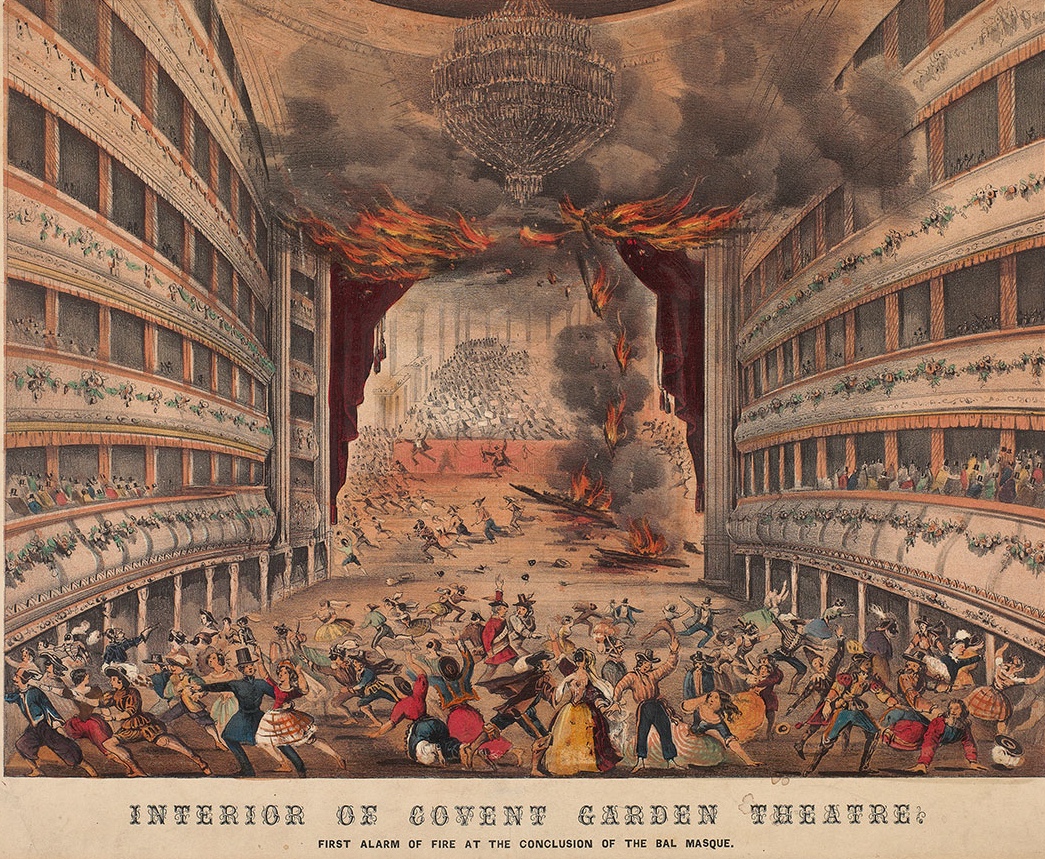

Interior of Covent Garden Theatre at the first alarm of fire (1850’s)

39.5 x 50 cm

Hand coloured print

S.14-2009

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The Covent Garden Theatre (today the Royal Opera House) originated in Davenant’s Duke’s Company which was the second company to have been patented for drama by Charles II in 1662. The first theatre on the Covent Garden piazza was built in 1728 and hosted Handel’s Messiah. It burned down in 1808 and was reopened the next year. This print shows the fire in the second theatre, on March 5th, 1856, during a Masked Ball given by “The Wizard of the North” John Henry Anderson, a professional magician who rented the theatre for his show at that time. Unlike the previous fire in 1808, this catastrophe did not involve fatalities – the public escaped - but the theatre was totally destroyed. The building which reopened in 1858 is the one still standing today.

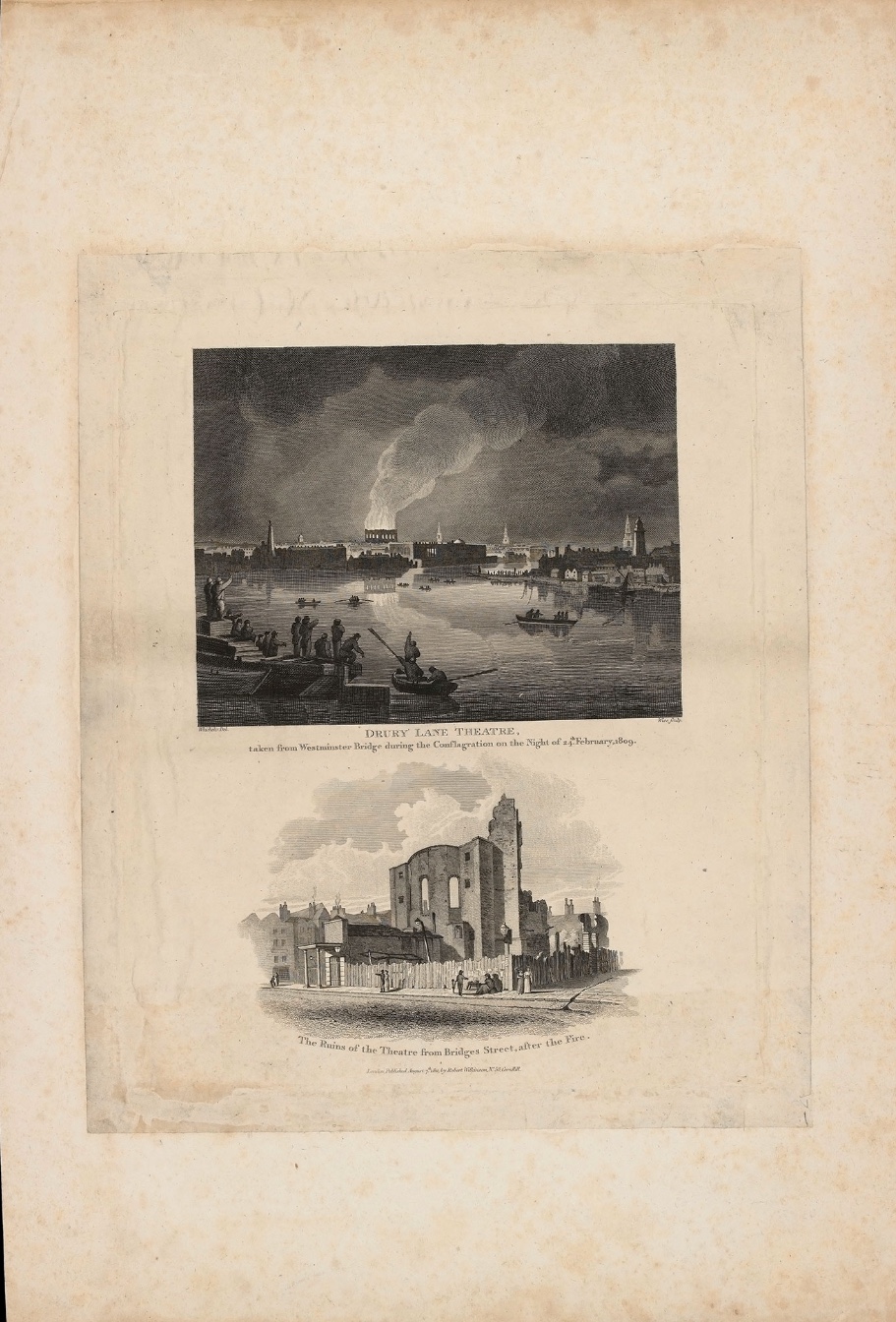

John Mayle MICHELO (1779-1865)

engraved by William WISE (1847-1889)

Drury Lane on fire on 24 February 1809

55.5 cm x 37 cm

Etching (1811)

Published by Robert Wilkinson, London

S.38-2008

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

As is the case with many theatres in Europe, Drury Lane has a long history of damage by fire. The first theatre (built in 1663) burned down in 1672; the new building reopened in 1674, and was destroyed in 1791 under Sheridan’s ownership and was replaced by a bigger building. Even this Henry Holland building, employing the cutting edge of fire protection technology, was not able to avoid this plague of theatres. Although it was fitted with the latest innovations such as an iron fire curtain and water tanks on the roof, the fire curtain had not been trialled for 2 years and the the water tanks were empty – having been more often used for dramatic effects on stage than for prevention of fire.

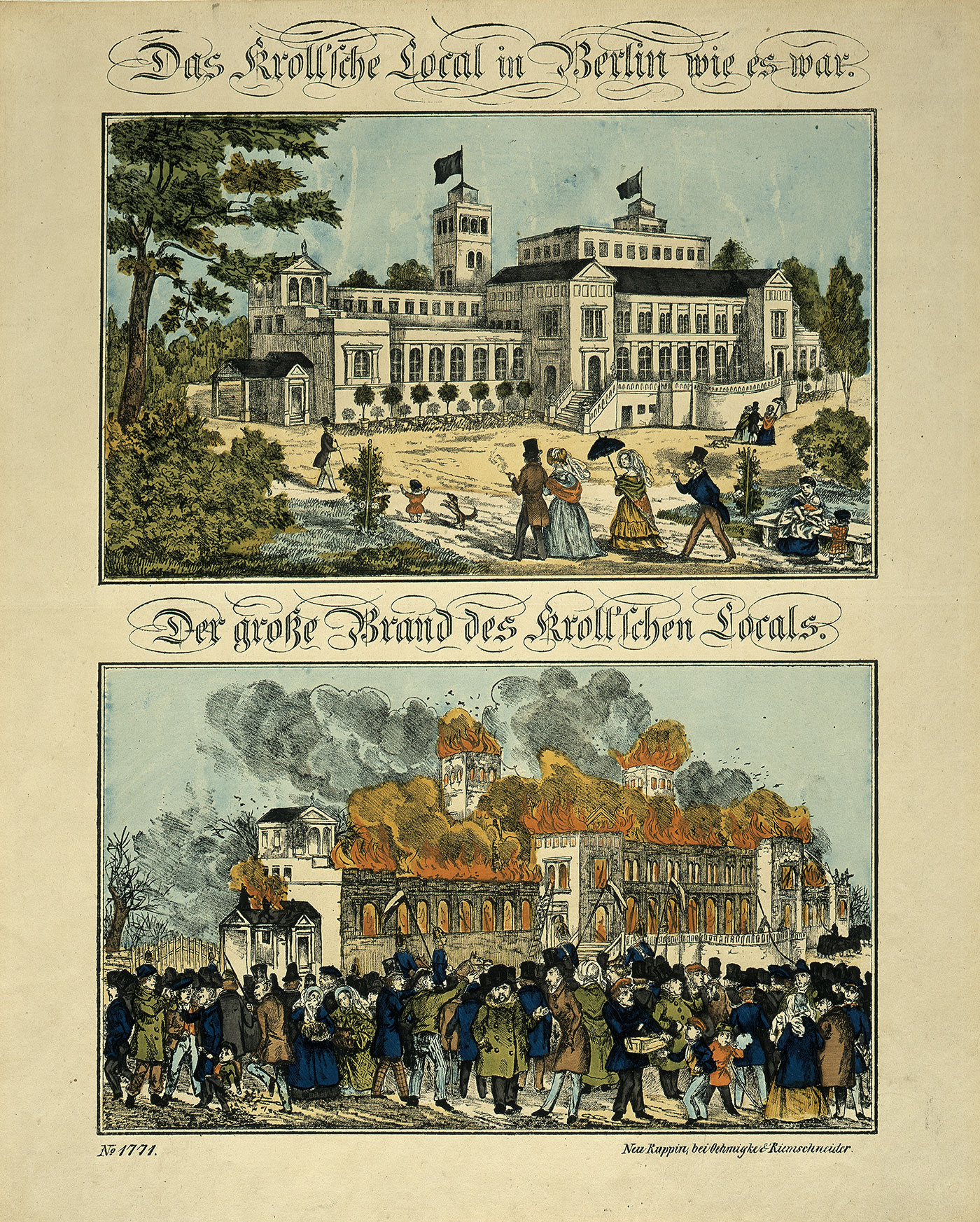

OEHMIGKE & RIEMSCHNEIDER (edition)

Kroll’sches Lokal, Berlin (c 1851)

41.8 x 33.4 cm

Lithography

VII 1093, F 8442

German Theatre Museum, Munich

“Bilderbogen” (sheet of pictures) with views of Kroll’sches Lokal before and during the fire 1851. Kroll’sches Lokal, later called Krolloper, was an entertainment complex offering a wide variety of amusements. In the theatre hall, comedies, operettas and some operas were performed at the time.

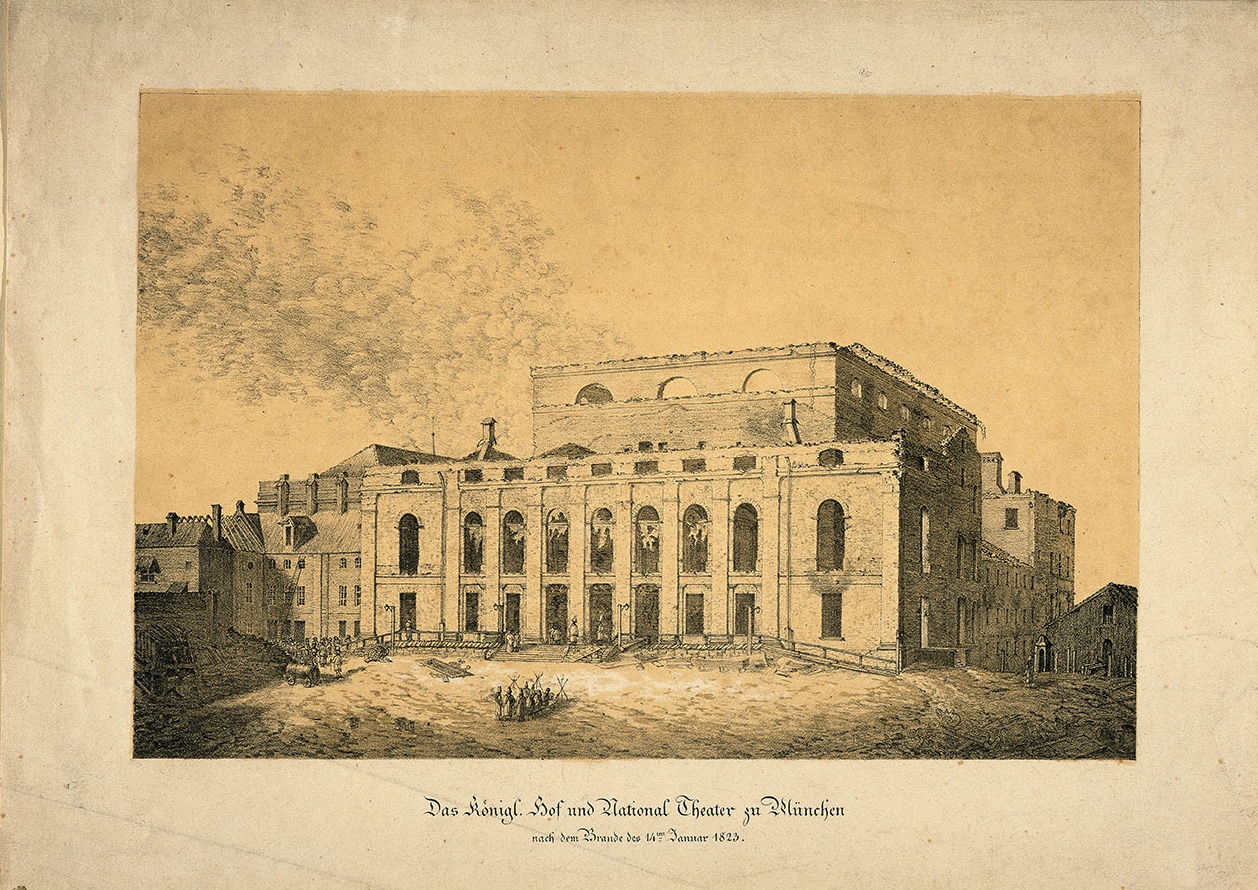

N.N.

Hof- und Nationaltheater, Munich (c 1823/24)

28.8 x 36.5 cm

Lithography

after watercolour by Joseph Karl Cogels

VII 2272, F 1546

German Theatre Museum, Munich

View of the Court and National Theatre, opened in 1818, after the fire on January 14th, 1823.

N.N.

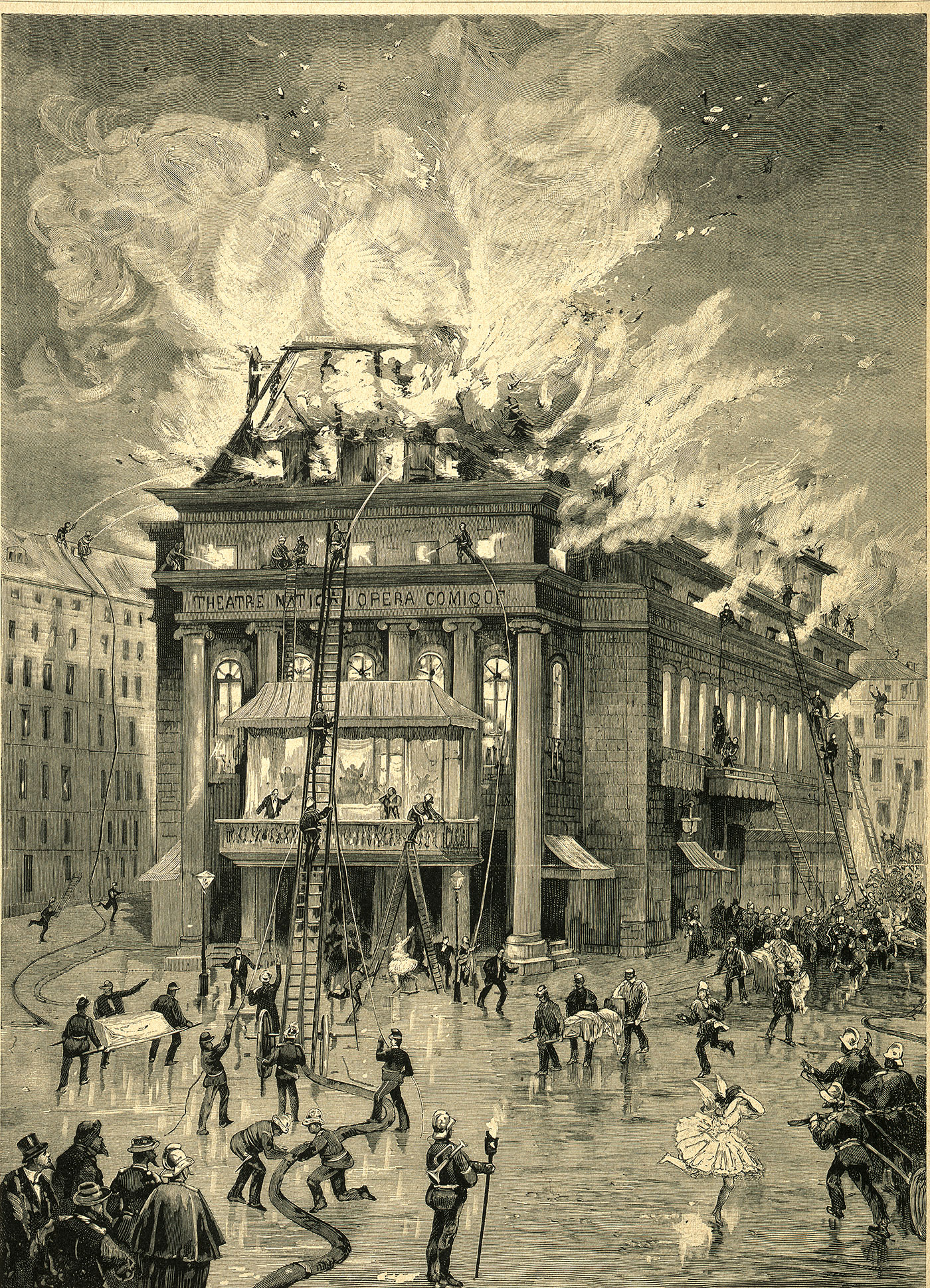

Salle Favart, Paris (1887)

37.4 x 27.2 cm

Wood engraving

Print from the journal “Allgemeine illustrirte Zeitung. Über Land und Meer”, (1887) 38, p. 726.

VII 3506, F 8443

German Theatre Museum, Munich

View of the second Salle Favart, later called Opéra Comique, Paris during the fire of 1887. “Carmen” and “Les contes d’Hoffmann” were performed here for the first time.

I. JAGODIC

The Estates Theatre on fire (1887)

40 x 30 cm

Oil painting

Photo by Matevž Paternoster

510:LJU;0019650

Museum and Galleries of Ljubljana

During the night between the 16th and 17th February 1887, the building of the Estates Theatre in Ljubljana burnt to the ground in a huge fire. In 1889 began the construction of the present day Slovenian Philharmonic building on the same site.

C. D. FRITZSCH (1765-1841)

View of Christiansborg Palace on fire (1794)

27.5 x 34 cm

Gouache

Inv. no. 1931:124

Courtesy of the Copenhagen Museum, Copenhagen

The theatre that did not burn: the Court Theatre in Christiansborg Palace, inaugurated in 1766, remodelled inside in the 1840s, and since 1922 home to the national Theatre Museum. Christiansborg Palace, which nowadays houses the Danish Parliament, used to be the King’s Castle for centuries. It was totally destroyed by fire in 1794 and again in 1884, to be rebuilt both times. The Court Theatre, situated in the right wing on the courtyard (the white building highlighted in the painting), miraculously survived both conflagrations. Today, the Court Theatre is a listed building and the most important object of the Theatre Museum.

The painter C.D. Fritzsch painted Copenhagen street life, often with a comic twist, as well as Copenhagen events like the palace fire in 1794, the big city fire in 1795 or the battle of 1801. Subsequently he specialized in flower paintings, becoming the best Danish artist of his time in this field.

Fires everywhere:

In London, a fire started in a workshop between the ceiling and the roof and ruined the Royal Italian Opera in Covent Garden during a ball in 1856 (the parterre is raised to the level of the stage to form one huge room).

Also in London, a fire reduced Drury Lane Theatre to little more than a wall in 1809, despite its iron curtain and large water tanks.

Both theatres were subsequently rebuilt.

In Berlin, an entertainment palace before and during a fire in 1851.

In Munich, ruins of the Court and National Theatre, incinerated in 1823.

In Paris, fire brigade fighting for the Opéra Comique in 1887.

All three theatres were subsequently rebuilt.

In Ljubljana, the Estates Theatre burned down in 1887; it was replaced by a concert hall.

In Copenhagen, one theatre that did not burn: when Christiansborg Castle suffered a fire in 1794, the Court Theatre in the right wing remained unharmed. Since 1922, it is home to the national Theatre Museum.

Vinzenz KATZLER (1823-1882)

August Stefan KRONSTEIN (1850-1921)

The Ring Theatre in Vienna: auditorium during the outbreak of the fire (1882)

23.8 cm x 32.3 cm

Newspaper cutting

GS_GBG6443

Theatre Museum, Vienna

On December 8th, 1881 the Ring Theatre in Vienna was almost sold out for the second evening of “The Tales of Hoffmann” by Jacques Offenbach. Unnoticed by the visitors the fire started on stage before the opera had even begun. One of the gas lamps was not ignited correctly, more gas effused, and the second attempt to get the gas lamp burning led to an explosion, which set parts of the decoration on fire. The growing heat on stage and under the roof of the stage house led to a detonation and the curtain blew up into the auditorium up to the balconies. The lights in the whole theatre building went out, while the flames and fumes entered the auditorium. Stampeding the people tried to get out but they hardly found the way to the doors in the complete darkness. The safety lighting was also not working because the oil lamps were empty.

N.N.

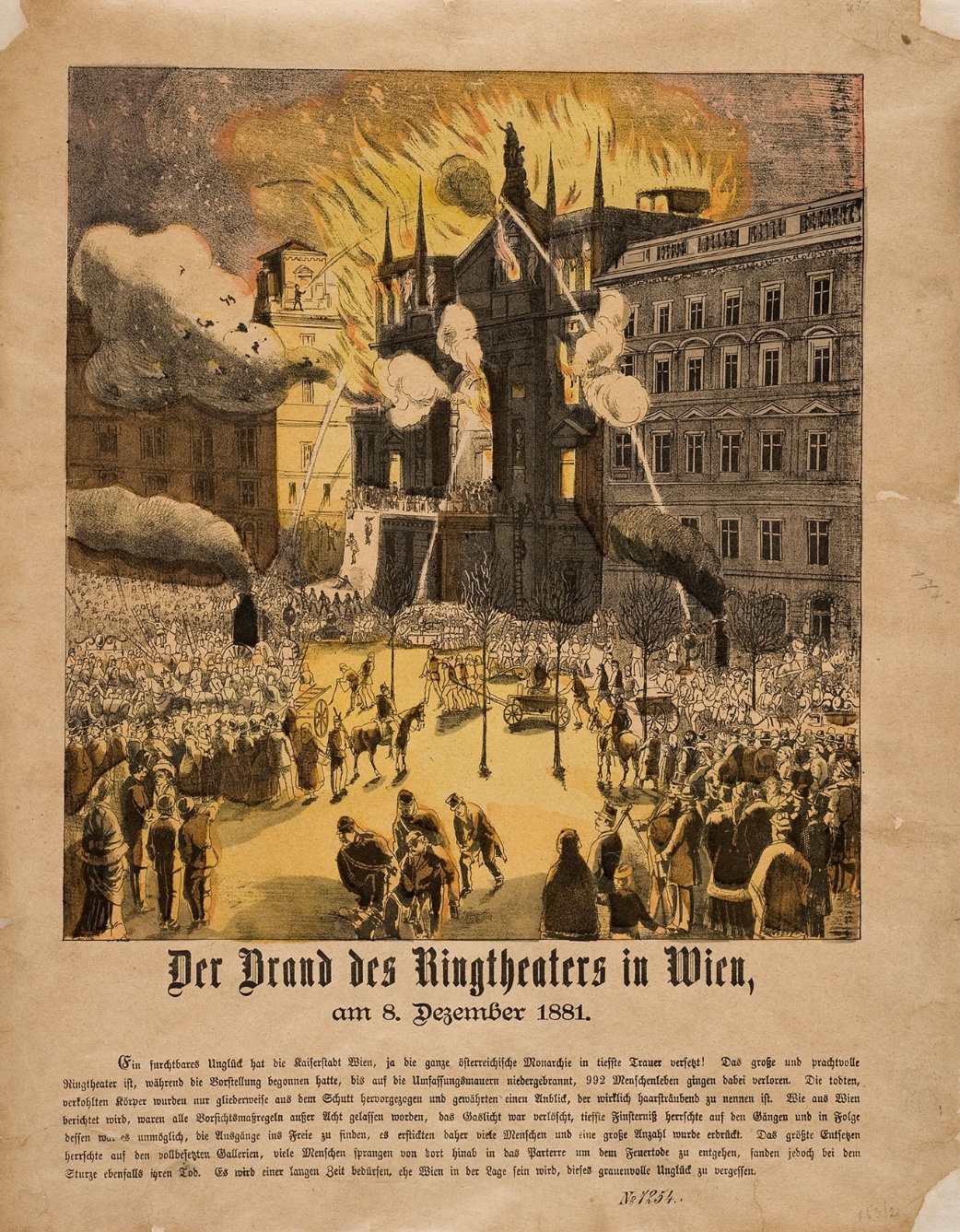

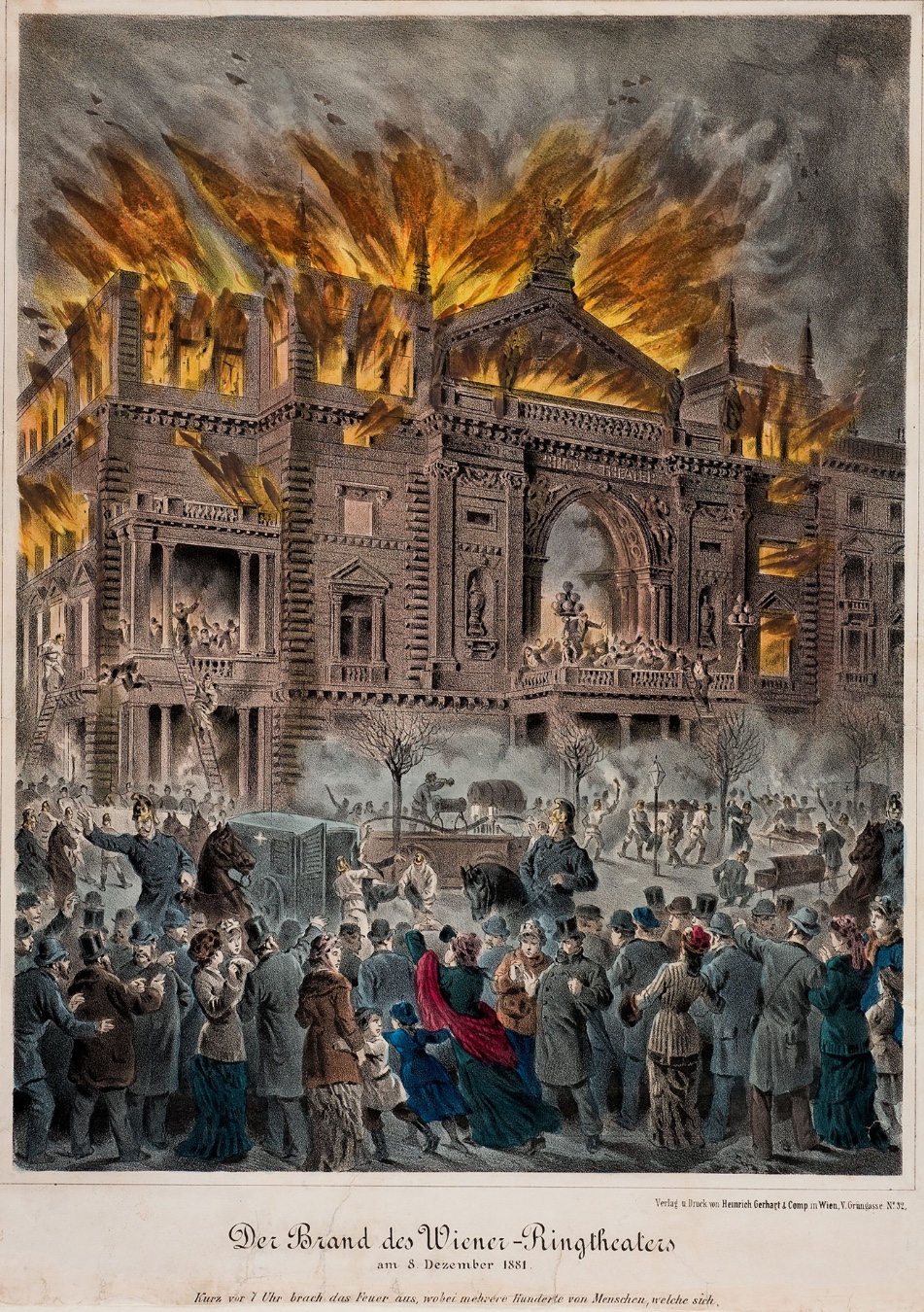

The fire catastrophe at the Ring Theatre in Vienna (1881)

41.5 x 32.7 cm

Coloured lithography on paper

GS_GBU3943

Theatre Museum, Vienna

Within the series of theatre fires in the 19th century the catastrophe at the Ring Theatre in Vienna was the worst – at least 450 fatalities – and let finally to legal consequences. Not only Vienna but the whole of Europe was shocked. Due to a trial and official investigation in 1882, the fire disaster was examined carefully and is documented very well. The trial started in April 1882 and ended in May. Accused were Julius von Newald(mayor of the city of Vienna), Franz Jauner (director of the Ring Theatre), Franz Geringer (facility manager of the Ring Theatre), Josef Nitsche (lighting technician of the Ring Theatre), August Breikthofer (fire guard at the Ring Theatre), Anton Landsteiner (superintendant of the police), Adolf Wilhelm (commander of the fire brigade) and Leonhard Herr (foreman of the fire brigade). Found guilty were only the members of the theatre Franz Jauner, Franz Geringer and Josef Nitsche. The members of the fire brigade and the police were acquitted – although the trial revealed mistakes on the side of the executive, too. But nevertheless a new and stricter theatre law for security and public order (Neues Theaterordnungsgesetz) was passed in 1882, including safety curtains, outwards-opening doors and fireproofing of the stage. Similar theatre laws and regulations in other countries followed.

N.N.

The fire catastrophe at the Ring Theatre in Vienna (1881)

51 x 38.2 cm

Coloured lithography on paper

GS_GBS3855

Theatre Museum, Vienna

Within the series of theatre fires in the 19th century the catastrophe at the Ring Theatre in Vienna was the worst because of at least 450 fatalities. There are several crucial points, which led to a disaster in this extent: The fire was not reported immediately, the people in the theatre were not informed in time, the emergency lighting was not working, the architectural structure of the building made the way out long and complicated, and the theatre staff was unable to cope with this case of emergency. When the police and the fire brigade finally arrived, they also worked insufficiently because they had not expected a fire to this extent. Even worse the head of the police mistook the situation and argued that there is no one in the theatre anymore because no one was coming out any longer, and he stopped the rescue operation. While still people crowded at the doors, which unfortunately opened inwards. The fire disaster was carefully examined in a trial afterwards and in summer 1882 a new theatre law for security and public order (“Neues Theaterordnungsgesetz”) was passed to avoid such catastrophes in future. Similar new laws in other countries followed.

Photo studio M. FRANKENSTEIN, Vienna

The Comic Opera in Vienna (c 1875)

11.3 x 17 cm

Photo on cardboard

FS_PBK148193

Theatre Museum, Vienna

In 1874 a new opera house opened in Vienna. Its original name Comic Opera (renamed Ring Theatre in 1878) made clear that it was a theatre meant to stage musical productions different from the ones at the Court Opera. The theatre was, like many other new prestigious buildings of that time, situated at the “Ringstrasse”, the boulevard which had been created around the city centre since 1857 and replaced the medieval city wall and its defensive grounds. The building site was quite small for an ambitious project of that size (capacity: 1,760 persons). The architect Emil von Förster tried to solve the problem by expanding the building in height (nine storeys, five tiers of seating) – which had fatal consequences during the fire catastrophe of 1881 because people who tried to escape from the galleries got lost in the winding corridors or stuck in the narrow staircases.

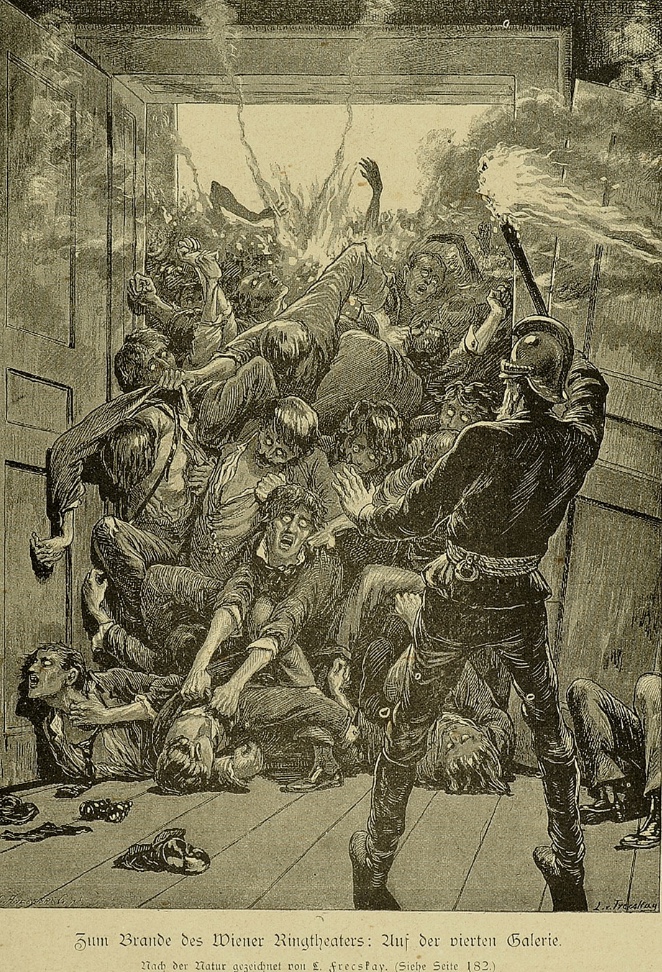

Laszlo von FRECSKAY (1844-1916)

On the fourth gallery (1882)

22.3 x 16.6 cm

Newspaper cutting

BIBT_RT_Ztg1_09

Theatre Museum, Vienna

Because of the Ring Theatre fire at least 450 people died. The most significant proportion of fatalities occurred among the visitors of the galleries, especially the forth gallery. These people had the longest and most complicated way out. They hardly found the doors because the light went out after the explosion on stage and the emergency lighting was also not working. The staircases had no windows to bring in fresh air or light from outside. Unfortunately, the two emergency staircases from the upper galleries have not been known to the public. Disastrously, some of the doors could not be opened anymore because they opened inwards and the crowd trying to get in panic out blocked them themselves. Most of the victims suffocated because of the fumes.

The Ring Theatre fire in Vienna, 1881, illustrated by contemporary newspaper sketches and photos. This tragedy was a turning point: as a result, all over Europe safety measures were reconsidered, fireproof materials and non-burning materials like iron and steel were introduced, gas light gave way to the recently invented electric light, and theatre architecture changed considerably.

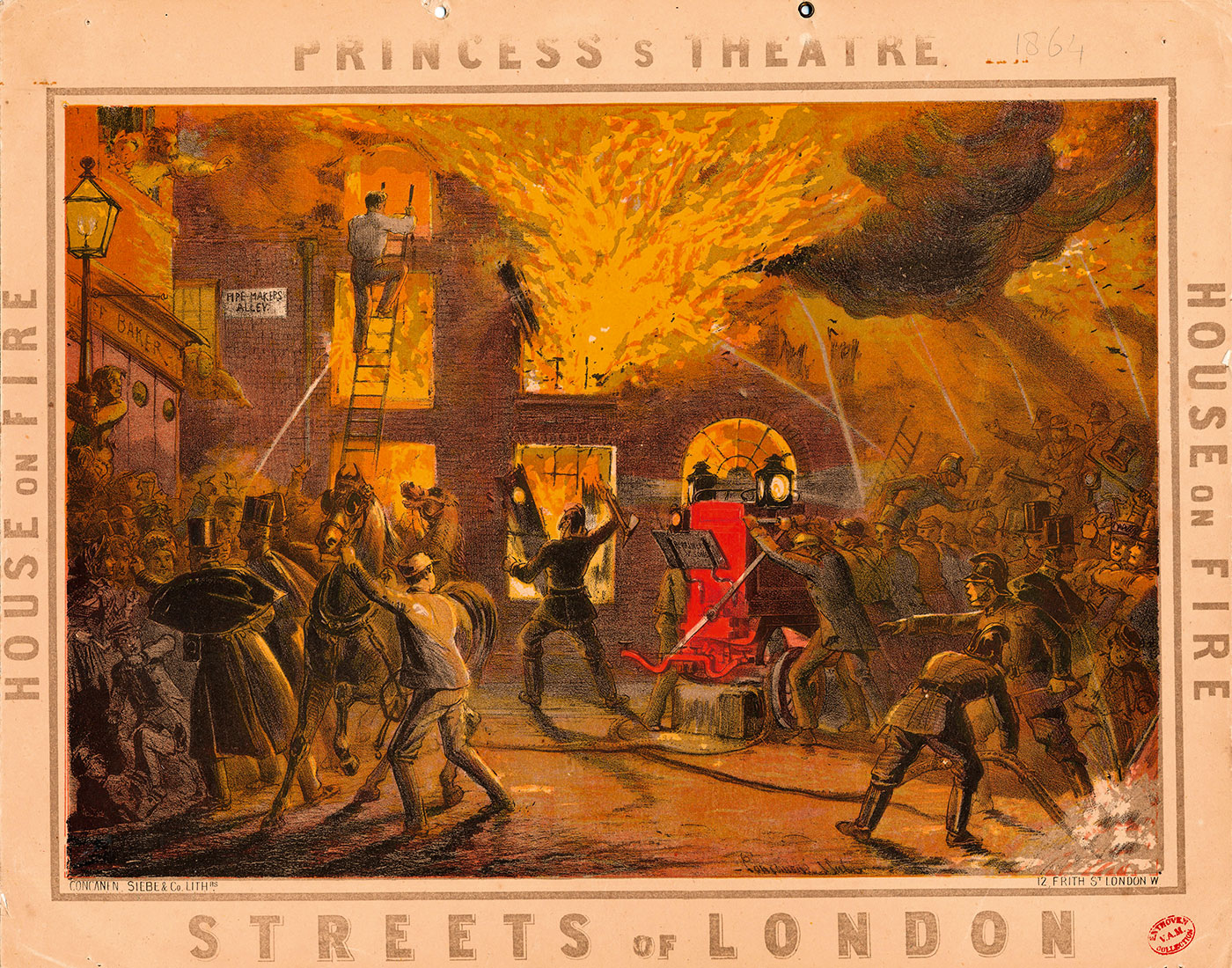

N.N.

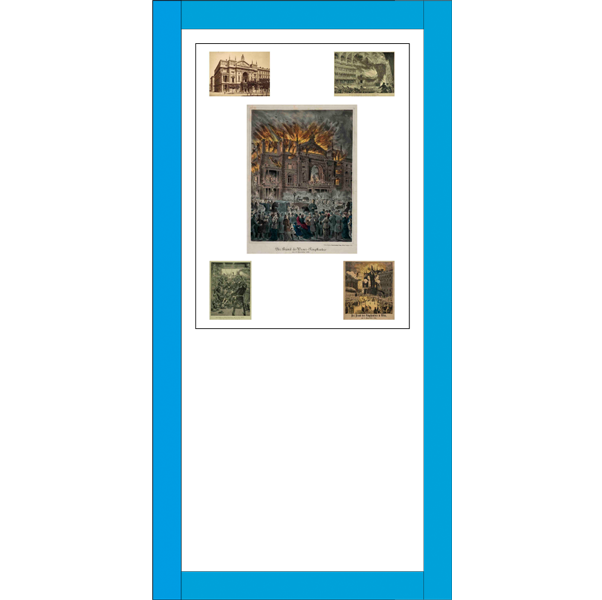

Advertising card for “Streets of London”, Princess's Theatre (1864)

33.2 x 41.2 cm

Paper, coloured ink, printing ink

Published by Lee CONCANEN

S.2520-1986

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

As opposed to other exhibits depicting theatres on fire, this advertising card shows fire deliberately created for dramatic effect, on the stage. The musical “Streets of London” was adapted for the London stage from Dion Boucicault’s “The Poor of New York”. One of the shows highlights was this scene of a house on fire – which given the theatre’s history one imagines would have brought a special frisson to the audience. Contemporary reviews noted that the emphasis in the show was on the special effects rather than the drama itself, which was not unusual in British theatre at the time.

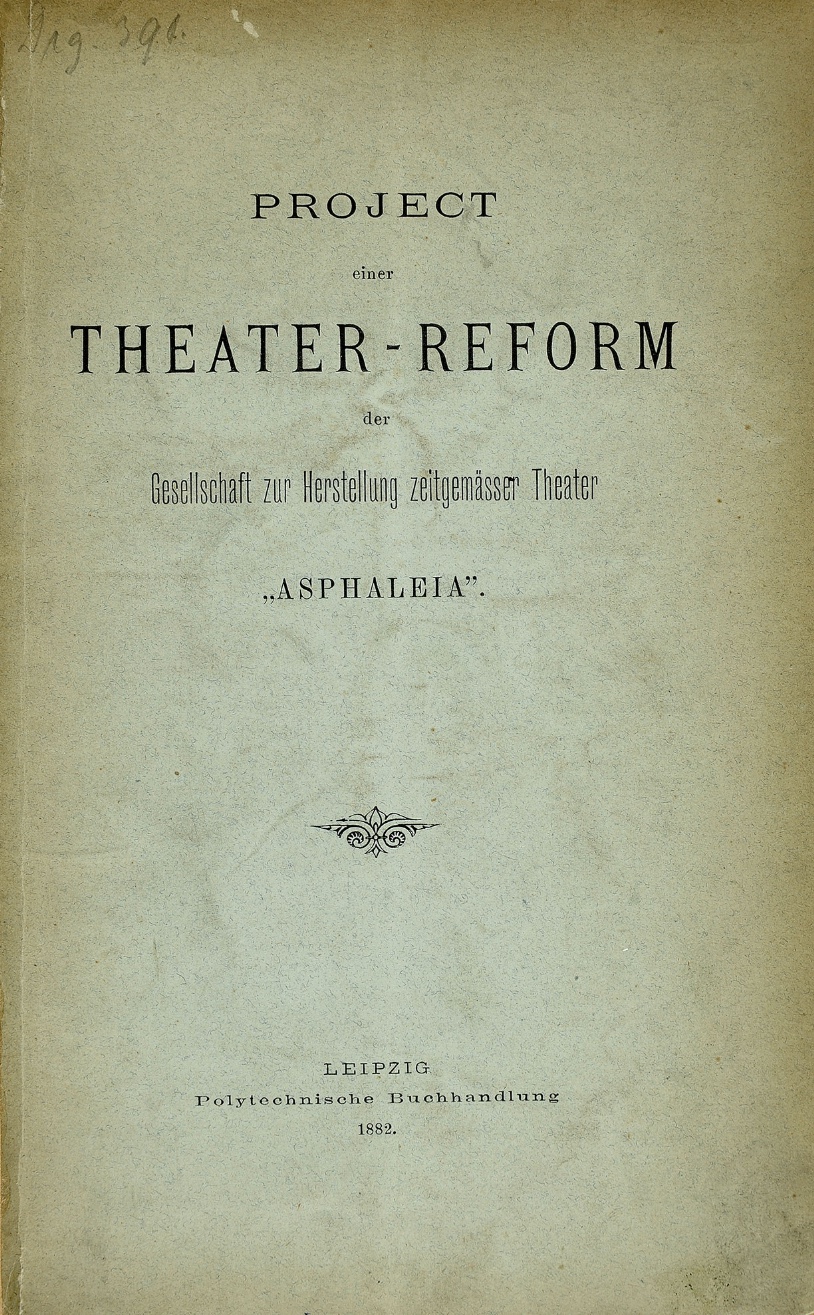

N.N.

Project for a theatre reform by the society for constructing modern theatres, “ASPHALEIA”

22.1 x 14.6

Letter print on paper

BIBT_621325_B_Th

Theatre Museum, Vienna

The society ASPHALEIA (Greek ασφάλεια meaning safety) was founded in Vienna immediately after the Ring Theatre fire in 1881 by the engineer Robert GWINNER (dates unknown) and the stage designer Johann Kautsky. Other architects and technicians of the time became members of this society, and together they postulated new standards for building secure theatres. In the following years these standards spread practically all of Europe. On the first pages of their book the authors make clear how building theatres had developed in the wrong way:

“Today’s theatre is still based on the principles to which it was built in the 17th century. The enormous technological progress in our days had no effect on theatre. […] Every novelty increased the contradiction between the old system and the modern requirements, therefore every novelty did not mean improvement but worsening. E.g. to make room for a larger quantity of people only the auditoriums were enlarged but not the hallways and staircases, they were left like two hundred years ago. Gas light was introduced, but the theatre building still was made of flammable materials. Even the auditoriums of the newest theatres are still made of wood, cardboard, wallpaper and other dangerous materials; the same is true for the drawing floor and the stage. And the under stage machinery is made from a whole forest, too.” (p.5-6)

According to ASPHALEIA, a real reform in building secure theatres had to observe four sectors: 1. Construction (free standing or with fire walls to the next building, stone and iron construction only instead of wood, wide hallways and staircases, more doors and windows, and doors to be opened outwards), 2. Technical equipment (safety curtain, stone and iron construction for the whole stage system, hydraulics for the stage machinery and for the movements of objects, fire extinguishing system, and ventilation and smoke outlets), 3. Decoration (cyclorama instead of wing and chariot system), 4. Lighting (electricity instead of open flames).

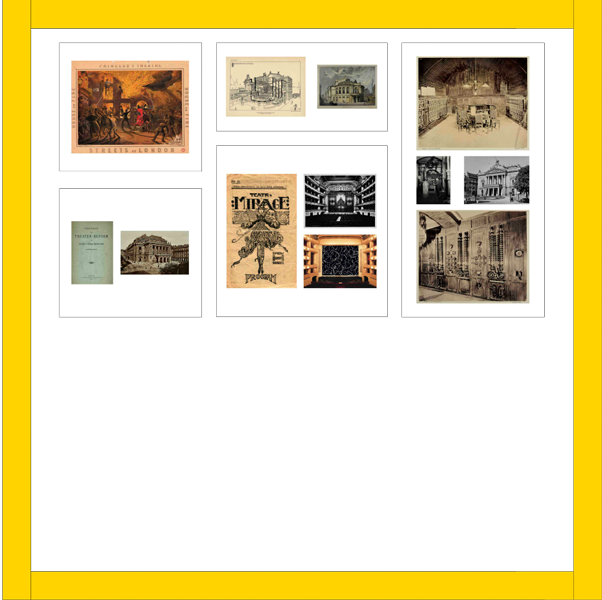

Mór ERDÉLYI (1866 -1934)

The Royal Opera House in Budapest (c 1910)

9 x 14 cm

Photo on paper

FS_PBP146232

Theatre Museum, Vienna

The opera house in Budapest opened in 1884 and was the first theatre to apply the new safety demands of the society ASPHALEIA. The architect Miklós Ybl designed the building, and the engineer and ASPHALEIA founder Robert Gwinner designed the stage machinery. True to the ASPHALEIA system, there was a hydraulic device for raising, lowering and tilting parts of the stage and working the flies, there was a cyclorama instead of backcloths, and there was a safety curtain. The system operated effectively for nearly a hundred years until it had to be dismantled for general refurbishment in 1984.

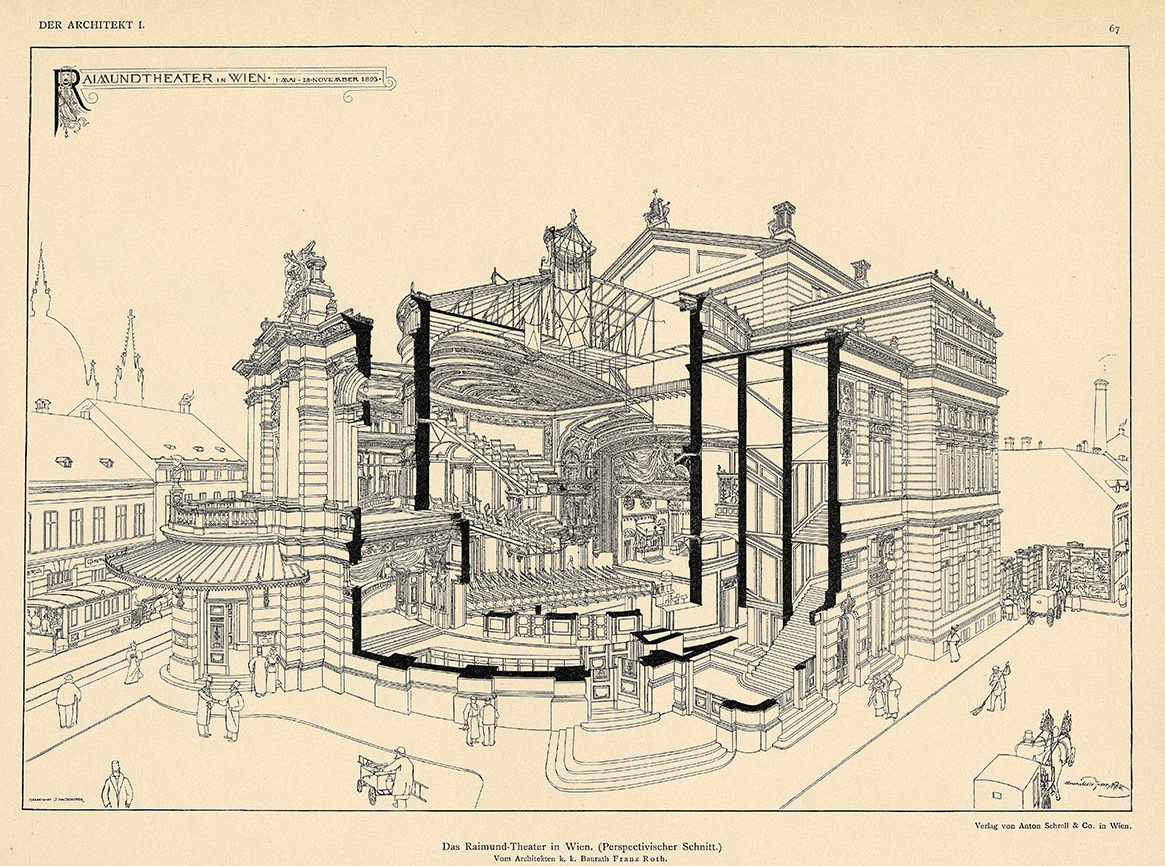

Franz ROTH (1841-1909)

The Raimund Theatre in Vienna (perspective section, 1893)

31 x 40.4 cm

Letter press on paper

106431

Wienmuseum

The Raimund Theatre, named after the Austrian dramatist Ferdinand Raimund, opened in 1893 and was the first theatre in Vienna to employ the ASPHALEIA system. The architect Franz Roth was member of the ASPHALEIA society and planned the building and its equipment according to their safety standards. The section shows how he realized the new standards: the theatre is freestanding, there is clear separation between spectators’ area and stage area, the hallways and staircases are designed very spaciously, there a six doors to leave the theatre easily, and many widows grant natural lighting and air supply. The theatre also had electric lighting only. Besides the new safety standards postulated by ASPHALEIA, Franz Roth was influenced by the architectural style of the most popular theatre architects of this time: Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer.

N.N.

The Raimund Theatre in Vienna (1893)

27.2 x 37.1 cm

Coloured wood engraving on paper

GS_GBG4565

Theatre Museum, Vienna

The Raimund Theatre, named after the Austrian dramatist Ferdinand Raimund, opened in 1893 and was the first theatre in Vienna to employ the ASPHALEIA system. The architect Franz Roth was member of the ASPHALEIA society and planned the building and its equipment according to their safety standards. The section shows how he realized the new standards: the theatre is freestanding, there is clear separation between spectators’ area and stage area, the hallways and staircases are designed very spaciously, there a six doors to leave the theatre easily, and many widows grant natural lighting and air supply. The theatre also had electric lighting only. Besides the new safety standards postulated by ASPHALEIA, Franz Roth was influenced by the architectural style of the most popular theatre architects of this time: Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer.

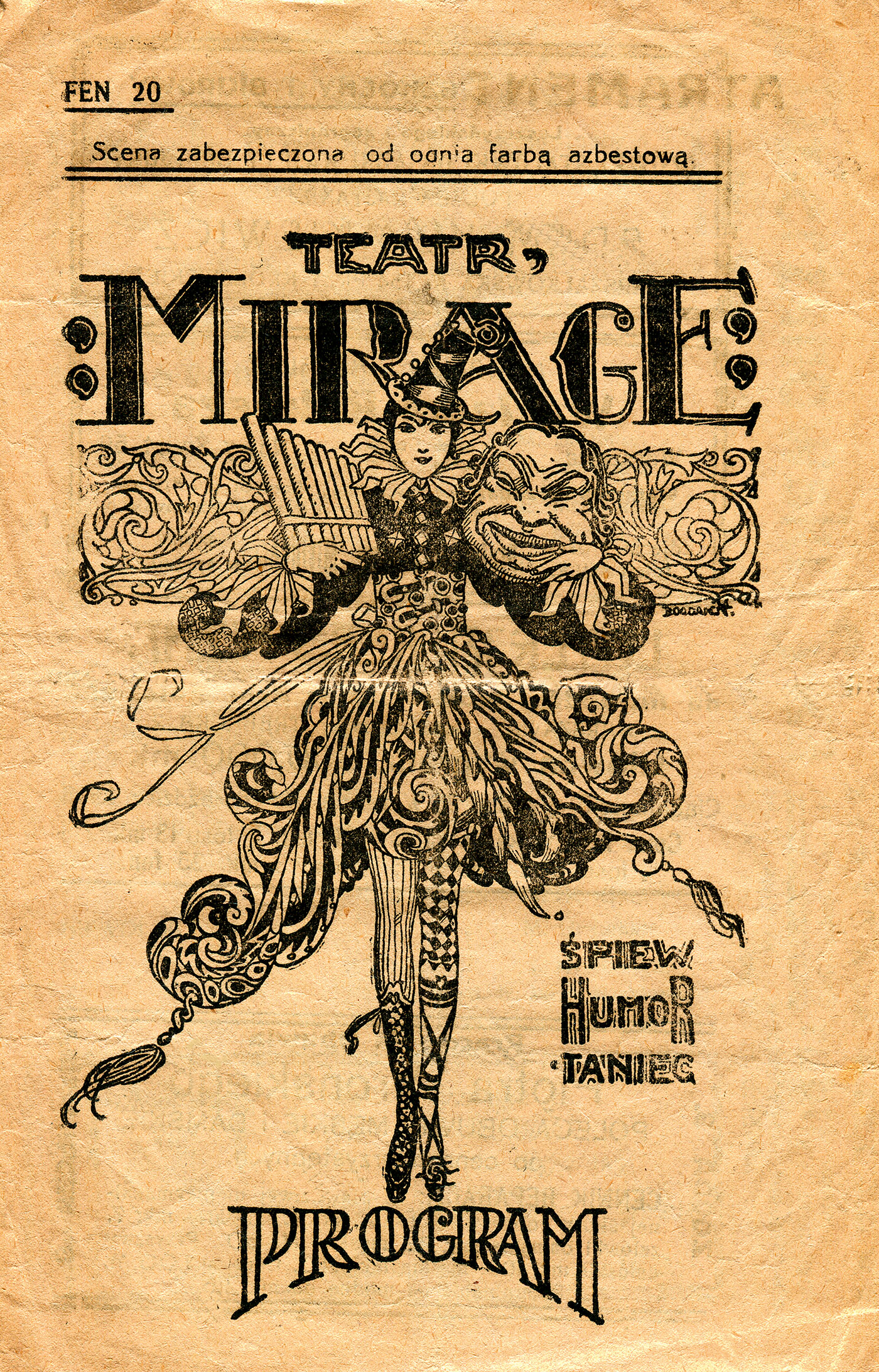

MIRAGE THEATRE

Programme (1915)

Print on paper

Theatre Museum in Warsaw

On the cover of the programme there is information about use of asbestos paint on the stage. However, this did not save the Mirage Theatre – it burned down completely in 1920.

Anton BRIOSCHI (1855-1920)

The first safety curtain of the Court Opera House in Vienna (1882)

16.5 x 22.5 cm

Photo on paper

by photo studio Alpenland, Vienna

FS_PBA93335

Theatre Museum, Vienna

The safety curtain according to the new standards was introduced at the Court Opera House in Vienna in 1882. The design for the original safety curtain by the theatre painter Anton Brioschi presents wrought iron fences with a portal of the park of the Belvedere Palace in Vienna. The motive refers to the function of the safety curtain: to separate one part of the building from the other.

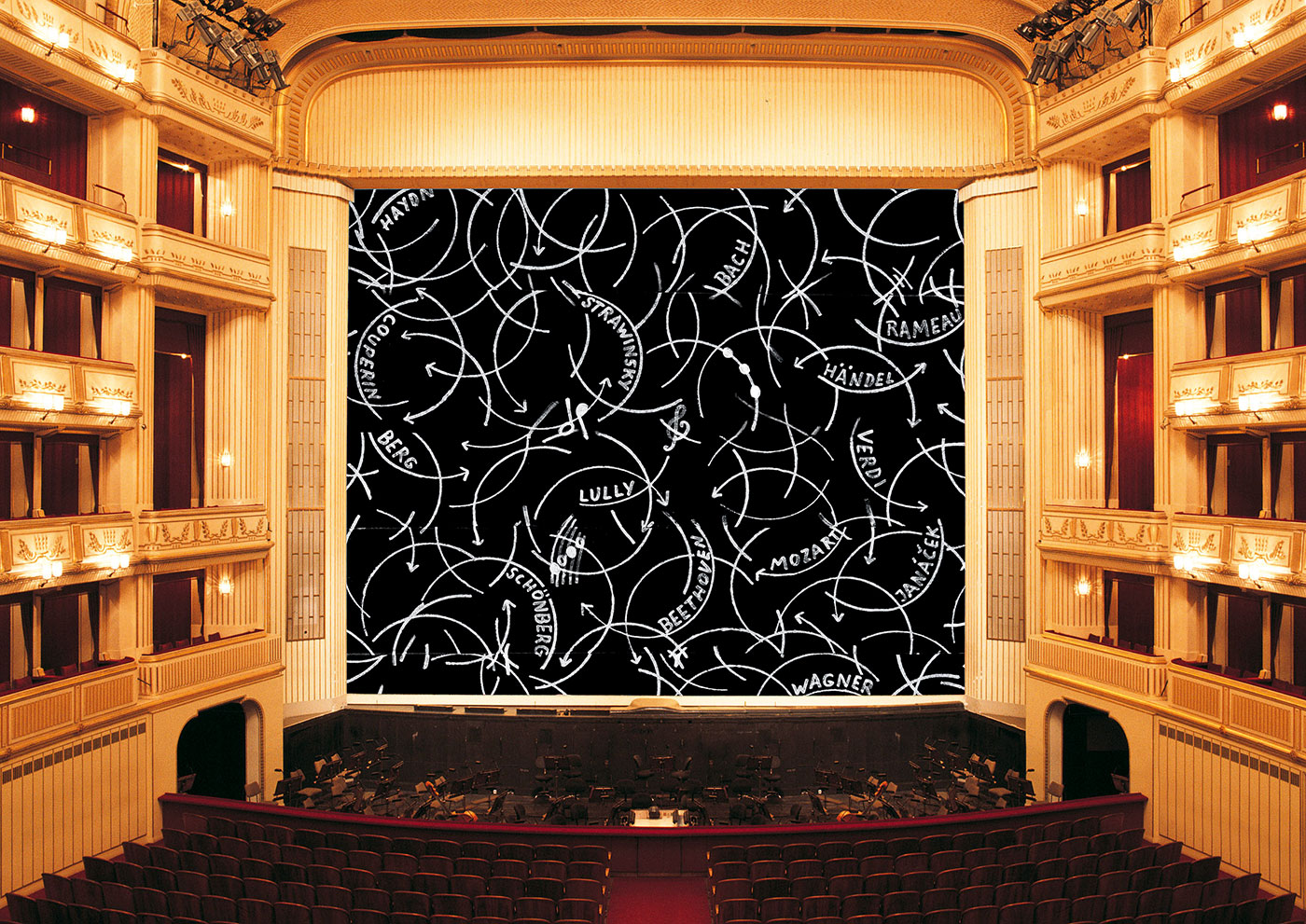

Oswald OBERHUBER (1931 -)

Exhibition series “Safety curtain” in the State Opera in Vienna (2013)

Digital photo

Provided by Vienna State Opera

Theatre Museum, Vienna

The Opera introduced the safety curtain in 1882. Since 1998, “Safety Curtain” has also been the name of an exhibition series at the State Opera in Vienna, which present every season a new design of an international renowned contemporary artist on the safety curtain of the opera house. Conceived by “museum in progress”, this project uniquely combines tradition and innovation. “Safety Curtain 2013/14” was created by the Austrian artist Oswald Oberhuber.

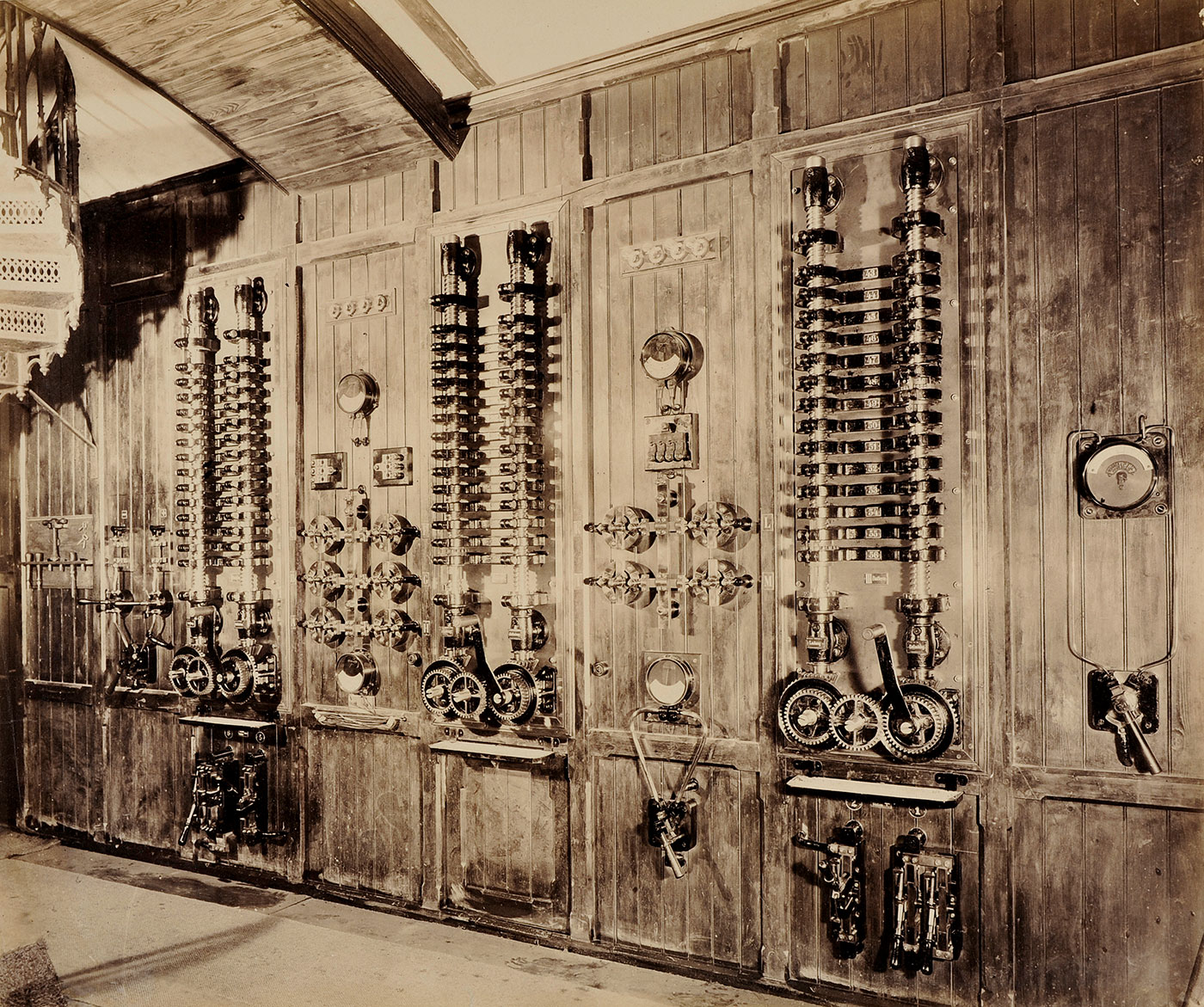

Carl GRAIL (dates unknown)

The Burgtheater in Vienna: switch room for the electric lighting (1894)

32.8 x 39.7 cm

Photo on cardboard

FS_PBUU266758

Theatre Museum, Vienna

The Burgtheater at the Ringstrasse opened in 1888 – seven years after the Ring Theatre fire catastrophe. Therefore the Burgtheater fulfilled from the beginning the new safety standards defined by the new theatre law that had been enacted in 1882, and also took into account the ideas of the ASPHALEIA society for theatre safety, founded also in 1882. Electric lighting in the whole building was one of the central postulations by ASPHALEIA to build theatres which are fire secure. In general one could say that the introduction of electric lighting at the turn of the century was the most important step towards more safety.

Photo studio WILLINGER, Vienna

The Opera House in Vienna: lighting chamber

16.8 x 11.9 cm

Photo on paper

FS_PBE63157alt

Theatre Museum, Vienna

The Opera House in Vienna introduced electricity in 1887. This also meant to change from gas lighting to electric lighting. Until today there are very strict rules concerning open fire on stage. On this photo also the candles are working by electricity.

Vinzenz CUNTZ (dates unknown)

The German Municipal Theatre in Brno

13.5 x 18.6 cm

Photo on paper

FS_PBE173074alt

Theatre Museum, Vienna

The German Municipal Theatre in Brno was, like many other theatres of that time, designed by the architects Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer. It opened in October 1882 with a production of “Egmont” by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. It was one of the first public buildings in the world lit entirely by electric light. The introduction of electric lighting was the most important step towards more safety and fire security. The theatre still exists, now called Mahen Theatre, after the Czech poet Jiří Mahen.

Carl GRAIL (dates unknown)

The Burgtheater in Vienna: switch room for the electric current regulation (1894)

32.8 x 39.7 cm

Photo on cardboard

FS_PBUU266758

Theatre Museum, Vienna

The Burgtheater at the Ringstrasse opened in 1888 – seven years after the Ring Theatre fire catastrophe. Therefore the Burgtheater fulfilled from the beginning the new safety standards defined by the new theatre law that had been enacted in 1882, and also took into account the ideas of the ASPHALEIA society for theatre safety, founded also in 1882. For the safety of theatres the introduction of electricity was the most important step, not only because of the electric lighting. It also made the controlling of the stage machinery easier and safer.

Burning theatres did not prevent authors and theatre directors from presenting big fires on stage, like the scene “House on Fire” in the melodrama “Streets of London”, a hit of the 1864 London season.

After the Ring Theatre fire of 1881, the society of theatre architects and technicians “Asphaleia” developed a safety stage. It was first realized at the Budapest Opera in 1884.

The most drastic measures concerned architecture: henceforward, different areas of the building were fitted with separate roofs and fire walls, and independent staircases were added for each floor (Raimund Theatre in Vienna, opened in 1893). Other measures included iron curtains, decorated to look less iron (Vienna Opera, 1882 and 2013), or asbestos materials, as advertised on the “Mirage” programme from Warsaw, 1915.

The use of electricity became compulsory for every theatre built after 1881. The first fully electrified theatre in Europe opened 1882 in Brno, now in the Czech Republic. As electric supply was just developing, theatres had to build their own power station and switch rooms, as seen here in the Burgtheater, Vienna, in 1894. In the “lights room” of the Vienna Opera in 1935, candles have become electrified, too.